In the North there was an attention to detail and naturalism that echoed the departure in art that we typically think of the Renaissance down in Italy. The two ‘re-births’ of art after the Medieval simplified compositions and composite characters lacking in anatomy happened relatively separately in Italy and in the “North” (though the the North becomes anything North of Italy). Because I will be covering the Italian Renaissance separately, here I can focus on the typical style of the Northern Renaissance which was not as immediately influenced by Classical Greek and Roman sculpture and the Neo-Platonist movement that worshiped the ideal. Instead, the North still had deeply seated religious values combined with extreme humanism and attention to naturalism. The naturalism is so extreme in some Northern Renaissance paintings that the human form (or occasionally animals) becomes un-real and grotesque. It’s pretty amazing. Below is an example of this in the Isenheim Altar by Matthias Grunewald. Jesus’ skin is so real that he can apparently be diagnosed with several skin diseases by modern doctors, but the effect of this uber reality is grotesque and exaggerated.

Matthias Grunewald, The Crucifixion

c 1515, oil on wood, 269 x 307 cm

Musee d’Unterlinden, Colmar

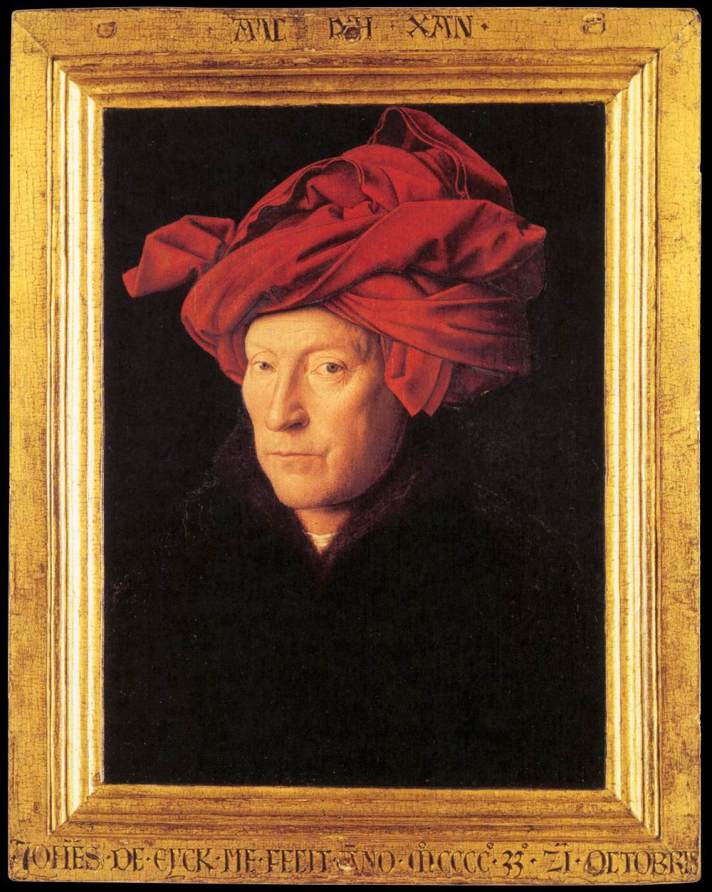

For the first of my formal breakdowns I am using a painting by one of the most prominent artists in the Northern Renaissance, Jan van Eyck. The painting below is a portrait generally accepted as his self-portrait.

This is a painting of a man with a very centralized, slightly vertical composition. The medium is oil paint, layered meticulously to create a rich color range, even in the blacks. The scale is quite small, at only 25.5 x 19 cm, but the detail is perfect. Within the composition there is a strong red shape that almost overpowers the wood panel, it is apparently a piece of fabric on the man’s head in a rough turban. There is some indication of contour line, but the detail is mostly defined with color variation and shading. The man in the painting is staring straight at the viewer, his body turned slightly away and so dark it almost completely blends into the dark ground plane. There is no descriptive background, instead all our attention is drawn to the identifiable facial features of this man with his red turban. The man’s face is so finely detailed that he becomes almost grotesque upon super close inspection with the tiny wrinkles and bloodshot eye rendered with extreme care. There is no attempt to idealize the sitter, though his expression is stoic as if he were painted while attempting to hold a perfect stillness. His eyes and expression do suggest an inner life that we haven’t seen since Ancient Rome. The drapery in the turban is extremely naturalistic and done in a beautiful warm red that can be achieved with oil paints.

Man in a Turban

Jan van Eyck, 1433

Oil on wood, 25.5 x 19 cm

National Gallery in London

Jan van Eyck painted this in 1433 after he and his brother invented oil paints. For the first time, red and rich blacks were achievable because there was no up-modeling with white. Instead, the color is painted layer over layer to create the illusion of density for shadow. The red turban doesn’t rely on white to make highlights so the red is really rich instead of turning pink. The perfect wrinkling of the skin and emphasis on his real tiredness and age contribute to the strength and magnetism of this subject. Here we see the Northern Renaissance attention to detail exemplified, every texture is carefully laid down in deliberate layers of paint. The focus on the face of the man because of the black surrounding him is basically new technology. With the invention of oil paint suddenly deep and beautifully spacious blacks are possible! In the Northern Renaissance (and later when those artists travel to Italy) we see the influence of oil paint on the color choices of painters. Saturated color with high contrast and tons of detail are typical of work after Jan van Eyck in these countries north of Italy.

Jan van Eyck was a Flemish painter in the early part of the Northern Renaissance who typified attention to detail and precise execution in his works. Not too much is known about the artist, but apparently the works which we can confidently attribute to him are from about 1430 to his death in 1441. The painting above is an example of portraiture that shows off his unflinching eye for naturalism, but there are other works which also show off his scientific rendering of plants and landscape. The Altarpiece of Ghent, one of his most famous works that is a great example of this naturalism, is probably a collaboration between himself and his assumed brother Hubert (we do not actually know for sure if Hubert was his brother or perhaps a different relation) that was finished by Jan after Hubert’s death. Just for fun, below is a progressively smaller detail from the Ghent Altarpiece starting with a single panel from the center which depicts the sacrificial lamb. (If you have some time, the Ghent Altarpiece is well worth checking out at this website, http://closertovaneyck.kikirpa.be/ where you can investigate every detail at several times life size to really get a feel for Eyck’s incredible meticulousness.) To give you an idea, the goblet catching the lamb’s blood is a little over 1.5 cm wide.

Jan van Eyck, details from Ghent Altarpiece

1432, oil on wood, 350 x 461 cm in total

Cathedral of St. Bavo, Ghent

In comparison, below is a portrait that may depict the artist Hans Memling in a self-portrait. It has been debated who the subject is, some think it was an Italian sponsor. In this portrait the composition is dominated by the central figure. The man has dark hair, a dark cap and dark clothing which help his face to be separated from the tranquil scene in the background. The landscape behind is idealistic and populated with exotic subject matter. The swans, the palm tree and the green rolling hills. In his hand, in the bottom right corner, is a coin with a face on it and there are laurel leaves half hidden at the bottom left edge of the piece. The composition is central and slight vertical orientation, like the portrait by Jan van Eyck above. There is little line, most forms are defined with light and shadow. The environment far in the distance is finely rendered complete with atmospheric perspective. There are clouds which appear translucent and wispy. The Roman coin and the exotic background that appears to be warmer weather suggest the setting isn’t the Flanders or Bruges landscape where the artist would have lived consistently through his life. The texture of this piece is smooth and the color is rich even in the atmospheric perspective that has historically gotten dusty and washed out. This indicates that the medium is probably oil paint, again. The expression on his face is also consistent with the Jan van Eyck painting and his features depicted in perfect detail. His gaunt appearance is not idealized and his hair is imperfect and slightly messy. There are fewer wrinkles than in the figure above, which can be attributed to the subject being younger or perhaps Italian Renaissance influence creeping in and changing the style of this very Northern Renaissance painter.

Portrait of a Man with a Roman Coin

Hans Memling, c 1480

Oil on oak panel, 31 x 23.2 cm

Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp

The man is carefully rendered to take up most of the composition and is framed by his dark clothing. The prop (coin) and the background, however, clearly put him in a more exotic location than Norther Europe. The palm tree looks pretty good so I think he had actually seen warm weather plant-life (unlike some other Northern Renaissance artists) but I’m not entirely upon first examination what the coin signifies. It appears Italian because of the wreath carefully painted on the tiny profile. His clothing is conservative and dark, not especially showing off his wealth or status.

Hans Memling was a very popular artist at his time and did both domestic and foreign commissions, which gives us a clue to the Italian landscape and the potentially Roman coin. Though occasionally the palm tree and coin have contributed to the notion that the subject is Italian, there is no real reason to positively conclude that the nationality of the man is Italian. When the work was originally attributed to Memling in the 19th century they did assume it was a self-portrait, although now we are not as sure. It’s possible the palm tree, coin and half-hidden laurel leaves comprise pieces of the subject’s family name.

My aim is to look at other self-representations (or likely candidates) to demonstrate some differences between Northern Renaissance style and Italian Renaissance style. These portraits demonstrate the attention to detail and typical color choices in northern painting. The other physical difference between the artistic styles that we should remember before moving onto the Italians is the size. Generally Northern Renaissance artists make smaller works, or the scale is small on a larger altarpiece (see Altar of Ghent above). We will see later that the Italians are not afraid of covering large walls with monumental figures. One more point about the representation of these people in their portraits, the emphasis is on their humanism and representing them as naturalistically as possible. Soon we’ll see in my post about the Italian Renaissance that representations of even people are idealized.

Below are three more examples of self-portraits by other Northern Renaissance artists to give you an idea of the consistency in their approach to portraiture and unflinching representation of the self:

Left:

Hans Holbein the Younger, Self-Portrait

1542 – 43 Coloured chalks and pen, heightened with gold put on later,

23 x 18 cm

Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

Center:

Simon Bening, Self-Portrait

1535- 36, Miniature on vellum (probably tempera) 9 x 8 cm

Musee du Louvre, Paris

Right:

Albrecht Durer, Self-Portrait

1500, Oil on lime panel, 67.1 x 48.7 cm

Alte Pinakothek, Munich

Citations:

Kuiper, Kathleen. The 100 most influential painters & sculptors of the Renaissance. New York, NY: Britannica Educational Pub. in association with Rosen Educational Services, 2010. Print.

“Past Exhibition: Memling’s Portraits.” The Frick Collection. N.p., n.d. Web. 21 Nov. 2013. <http://www.frick.org/exhibitions/past/2005/memlings-portraits>.

“Web Gallery of Art, image collection, virtual museum, searchable database of European fine arts (1000-1900).” Web Gallery of Art, image collection, virtual museum, searchable database of European fine arts (1000-1900). N.p., n.d. Web. 21 Nov. 2013. <http://www.wga.hu/framex-e.html?file=html/m/memling/3mature1/19coin.html&find=self-portrait>.